Key Takeaways

- No sweeping AI shock yet: U.S. job distribution is shifting at a normal historical pace.

- Sector shifts aren’t new: Information, finance, and professional services are moving faster, but their volatility predates AI.

- History puts it in perspective: Job reshuffling in the 1940s–50s was far greater than today’s.

- Young workers not clearly squeezed: The gap between recent and older graduates remains narrow.

- Exposure vs. usage show stability: Both OpenAI and Anthropic data point to little change in job disruption.

- Biggest users are coders and creatives: AI use is concentrated in computing and media, not clerical or production jobs.

- Data gaps remain: Broader, privacy-safe data from major AI providers is needed to track real impacts.

- The bottom line: The Yale study finds no evidence of an AI-driven jobs disruption so far.

Table of Contents

Almost three years after ChatGPT’s release, a new analysis of federal employment data finds the distribution of jobs across occupations is changing at a historically typical pace, and while some sectors are reshuffling faster than others, the economy shows no sign of a sudden AI-driven shock.

What the Study Measures

The new analysis, conducted by The Budget Lab at Yale, uses the U.S. Current Population Survey to track how workers are spread across occupations and how far today’s distribution has moved from an earlier starting point.

Its primary metric is a dissimilarity index. In everyday terms, it asks: what share of workers would have to switch occupations for today’s job landscape to look like it did before? The index is built from CPS data and averaged over twelve months to smooth out monthly noise. It tells us how much the job landscape has changed, not why it changed.

To connect this directly to AI, the study compares changes since November 2022 (the public release of ChatGPT) with earlier baselines, and pairs the CPS analysis with AI-specific datasets on occupational exposure (from OpenAI) and usage (from Anthropic) to see whether AI-heavy jobs are gaining or whether unemployment is concentrating in AI-exposed roles.

Is the Post-ChatGPT Period Unusual?

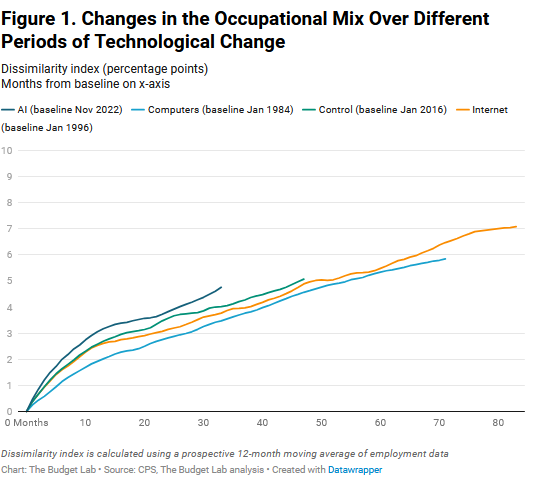

According to the analysis, the past 33 months look a lot like earlier technology waves. Compared with the rollout of the commercial internet and the spread of personal computers, today’s line is only a little steeper, about 1% point faster than the late-1990s path, and still well within past experience.

During the early internet years the job distribution in 2002 was only about 7% points different from 1996, meaning seven out of 100 workers would have needed to change occupations to match the earlier labor market.

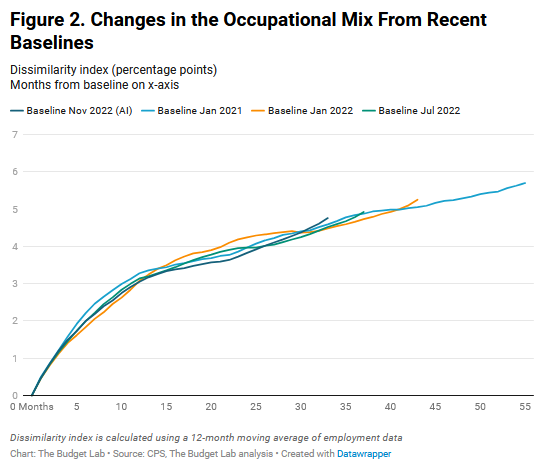

To ensure the study’s relevance to today’s labor market, the researchers also tested earlier starting points, January 2021, January 2022, and July 2022, all before generative AI went mainstream. The results looked almost identical. The curves from those baselines track closely with the November 2022 line, showing that much of the movement was already in progress. Taken together, the evidence suggests AI has not yet accelerated job reshuffling across the wider economy.

Where the Shifts Are Largest

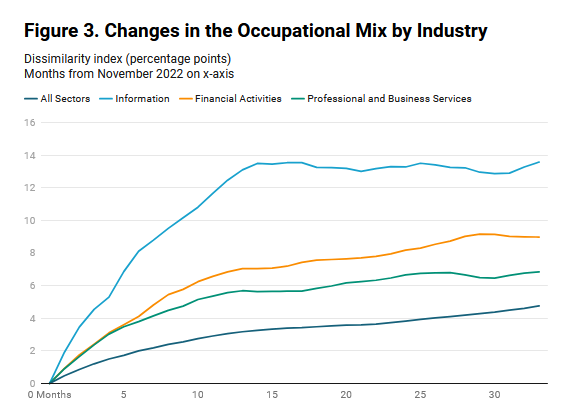

Breaking the data down by sector shows that some parts of the economy are moving faster than others. Since late 2022, information, financial activities, and professional and business services have all seen bigger changes in their job mix compared with the economy overall, with information showing the steepest rise.

However, the chart also makes it clear that these shifts did not begin with AI. The information sector, in particular, has long been prone to sharp swings, and its current path looks like a continuation of that pattern rather than the fingerprint of a single new technology.

What History Tells Us: Today’s Shifts Are Mild by 1940s–50s Standards

Looking further back puts today’s changes in perspective. Economist Jed Kolko notes that the U.S. job mix shifted much more dramatically in the 1940s and 1950s, when war and rapid industrial change were remaking the economy. By comparison, the past three years look relatively calm.

Kolko also cautions that the long-run balance of automation and AI is still unknown: these technologies may create as many jobs as they displace, or not. For now, though, the evidence suggests today’s job reshuffling is part of a familiar historical pattern rather than a sharp break from it.

Are Young Graduates Getting Left Behind?

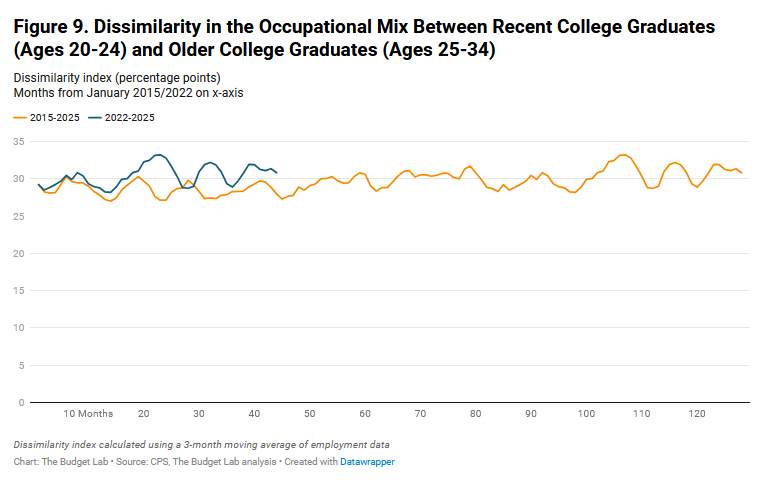

The report also looks at whether recent college graduates are being pushed out of certain occupations. It compares workers aged 20–24 with slightly older grads aged 25–34. The data show a small increase in differences between the two groups in recent months, but since 2021 the gap has mostly stayed within a narrow 30–33% range.

That uptick could just as easily reflect how early-career workers are more vulnerable to a cooling job market as it could any impact from AI. And because the sample size for recent graduates is relatively small, the results should be read with caution.

Exposure vs. Usage: Two Ways of Looking at AI’s Impact

The study also draws on two outside datasets to test how much AI may be affecting jobs. One, from OpenAI, measures exposure, meaning how much of an occupation’s tasks could, in theory, be sped up by at least 50% using GPT-4 or similar tools. The other, from Anthropic, measures usage, meaning how people are actually applying its Claude model in different occupations.

OpenAI’s exposure measure paints a picture of stability. Since early 2023, the share of workers in each exposure group has barely moved. About 29% are in the lowest-exposure group, 46% are in the middle, and 18% are in the highest. Among unemployed workers, exposure levels average 25 to 35% of tasks, no matter how long people have been out of work. In short, the numbers have held steady rather than rising.

If the missing tasks are instead counted as having zero usage, the picture shifts. Under that stricter approach, only about 3% of workers appear in jobs dominated by automation and virtually none in jobs dominated by augmentation. Even then, the shares stay flat rather than rising.

In both cases, the message is the same. Despite all the hype around AI adoption, neither exposure estimates nor usage patterns show clear evidence of accelerating disruption across the labor market.

Who Is Using AI the Most Right Now?

Actual AI use is concentrated in a few fields. Jobs in the “computer and mathematical” category account for most of the activity, with arts and media also using these tools more than expected.

By contrast, clerical and production jobs often look highly exposed in theory but show very little real usage in practice. When researchers compare exposure (what AI could affect) with usage (where AI is actually being applied), the overlap is weak. High-usage jobs tend to be clustered in scientific, technical, and business roles, while low-usage jobs are mostly in production and other work with limited computerization.

Data Gaps and Why They Matter

OpenAI’s exposure scores show what AI could potentially change, but they remain theoretical. Anthropic’s usage data, meanwhile, reflects only one model’s users and only part of the task spectrum. Other tools such as Copilot, Gemini, and ChatGPT, along with API activity, would likely give a much fuller picture of how AI is spreading through workplaces.

The report emphasizes that without better information, it is difficult to measure AI’s true impact on jobs. What is needed is comprehensive but privacy-safe usage data from all of the major AI providers, covering both consumer and enterprise accounts.

It is worth noting that Anthropic has set a useful precedent by publishing detailed metrics, yet broader industry participation will be essential to track how AI adoption is really unfolding

The Bottom Line

The study shows that despite the anxiety and hype surrounding AI, there is still no evidence of a sweeping disruption in U.S. employment since ChatGPT’s launch. The overall distribution of jobs across the economy has not shifted faster than it was before AI arrived, and the sectors showing the most movement were already in flux well before late 2022.

That does not mean bigger changes are off the table. History shows that general-purpose technologies tend to reshape work slowly, unevenly, and over the course of years or decades.

For now, the most important step is continued monitoring by tracking industry job patterns, exposure and usage levels, and outcomes for new workers, so that when real shifts begin to emerge, the data will show it.

Read More: OpenAI Hits $500 Billion Valuation in Secondary Share Sale, Overtakes SpaceX