Table of Contents

The U.S. Federal Reserve’s research arm is calling for cryptocurrencies to be treated as a distinct asset class in derivatives risk models, arguing that their price swings and stress periods differ so sharply from traditional markets that they no longer fit inside existing commodity or foreign-exchange categories.

In a discussion paper, Fed staff examine how crypto could be incorporated into the standard model banks use to calculate collateral for uncleared derivatives. Their conclusion is that crypto should sit in its own risk class within the ISDA Standardized Initial Margin Model (SIMM), a change that would likely raise margin requirements for many crypto-linked trades.

SIMM at the center of post-crisis risk controls

SIMM is the main tool major market participants use to estimate potential 10-day losses on portfolios of uncleared swaps and other derivatives, in line with post-2008 rules that require large firms to exchange initial margin on such trades. The model underpins the vast majority of collateral posted in the uncleared market, which has stabilized in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

When SIMM was originally put together, crypto assets were barely visible. Since then, the sector has expanded into a multi-trillion dollar market, with bitcoin and ether accounting for the bulk of outstanding value and U.S. dollar stablecoins playing a central role in trading and settlement. The paper argues that this growth makes it increasingly hard for risk managers to ignore crypto when they assess margin needs for complex portfolios.

Regulators such as the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission have generally treated major tokens as commodities for legal purposes. The Fed authors, however, focus on empirical behavior rather than legal labels and find that crypto’s statistical profile sets it apart from commodities such as oil, metals, and agricultural futures.

Crypto stress periods diverge from commodities

Using data on 10-day returns, the researchers study the most volatile quarters for cryptocurrencies and compare them with stress windows in traditional commodity indices. They report that the periods of maximum market turbulence for the two groups hardly overlap. Episodes that rocked digital assets did not coincide with the main stress phases in the S&P GSCI commodity benchmark, and vice versa.

That lack of shared stress history is central to their argument, as SIMM is built around the idea that each risk class should group instruments with comparable behavior under pressure so that a single set of risk weights and correlations can be applied. If crypto and commodities experience their worst losses at different times, the paper contends, folding them into a single bucket risks making measured losses look smaller than they could be on portfolios heavy in crypto.

The authors also note that cryptocurrencies are inseparable from their technological base, as they exist only on distributed ledgers and rely on specific market infrastructure, custody arrangements, and trading venues. These structural features further distinguish them from physical commodities.

Separate treatment for floating coins and stablecoins

To reflect those differences, the paper proposes adding a separate “cryptocurrency” risk class and product class to SIMM, with two internal segments.

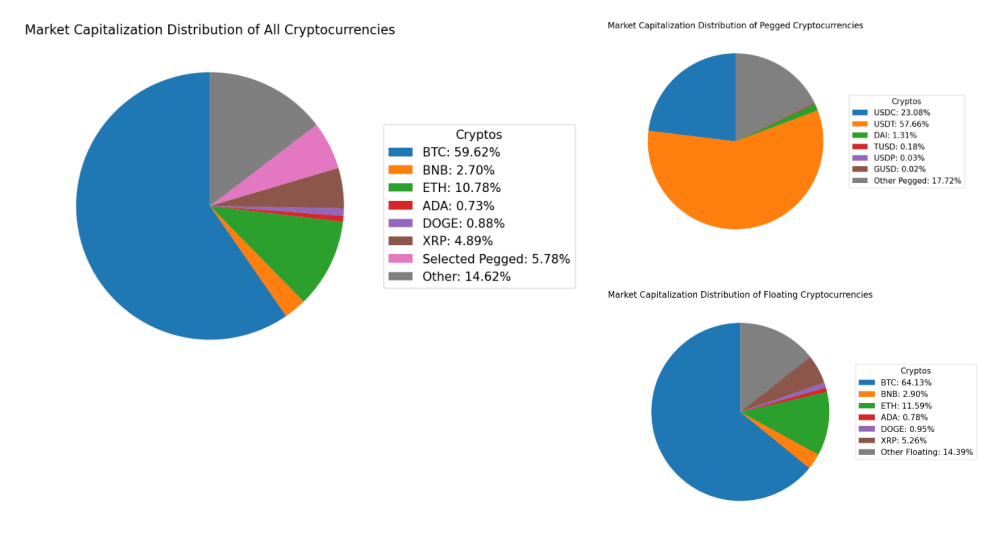

One segment would contain floating, unpegged coins, such as bitcoin, ether, and other highly volatile tokens. The other would be reserved for pegged assets, mainly dollar-based stablecoins like Tether and USD Coin, which aim to maintain a near-constant value against the U.S. currency.

For calibration, the authors rely on a representative set of large tokens that span most of the market’s capitalization. For floating coins, they use a broad crypto index as a proxy for overall behavior.

According to the paper, stablecoins require a different treatment, since their returns are typically tiny and driven by peg deviations and credit concerns rather than price trends.

The study finds that correlations within the floating segment are high, reflecting the tendency of major coins to move together in risk-on or risk-off episodes. Meanwhile, stablecoins display much weaker internal correlation once their dollar peg is taken into account, suggesting that their risk is more idiosyncratic.

Higher risk weights and limited diversification benefits

A key outcome of the exercise is a set of risk weights and correlations the authors believe would better capture crypto risk inside SIMM.

If crypto were simply dropped into the existing commodity risk class, the implied risk weight for floating coins would be relatively modest. However, when the team instead attempted to identify stress windows specific to crypto and calibrated a dedicated risk class, the recommended risk weight for floating coins more than doubled, while pegged coins received a much lower risk weight to reflect residual volatility and peg risk.

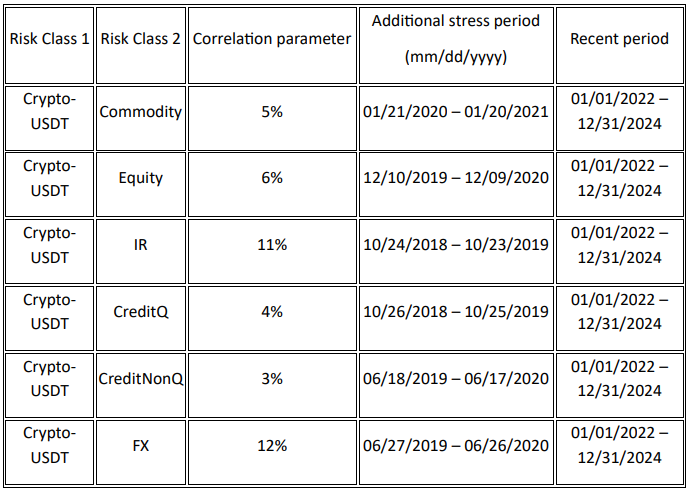

Correlations between the two crypto segments come out near zero, and cross-asset correlations between crypto and the six existing SIMM risk classes are mostly very low percentages. In practical terms, that means crypto exposures would offer little diversification benefit against equities, rates, credit, commodities, foreign exchange, or other existing classes when firms calculate margin.

The paper also relies on a “greedy” algorithm, already built into SIMM’s global calibration, to select the time windows when markets are most volatile in each segment. Since crypto trading is focused on only a few tokens, the authors argue this method is simple to run and produces stable estimates.

Regulatory impact and next steps

From a supervisory perspective, the message is that crypto risk should be quantified on its own terms rather than absorbed into other categories for convenience. If the recommendations were adopted by ISDA and regulators, banks with significant uncleared crypto derivatives could be required to post more initial margin, especially for positions in volatile coins.

That would reinforce existing efforts by global standard setters and national authorities to insulate the traditional financial system from extreme swings in digital-asset prices. It would also sit somewhat uneasily with legal precedents that describe Bitcoin and similar tokens as commodities, underlining the gap between statutory classification and risk modeling.

The authors stress that the views expressed in the paper are theirs alone and do not represent official policy of the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors. Even so, the analysis gives market participants an early look at how one key institution is thinking about digital assets within the main collateral framework for non-centrally cleared derivatives.

As crypto markets continue to evolve and regulators debate how far to bring them within the perimeter of existing rules, the Fed staff’s proposal points toward an outcome in which digital assets occupy a clearly marked, separate corner of the derivatives risk map rather than being treated as just another part of the commodity market.